book covers we love

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man is one of the most influential pieces of 20th-century literature, as well as being a masterpiece in its own right.

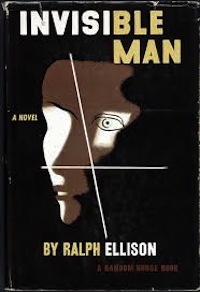

Since its original publication, it has been reprinted, translated, repackaged and reformatted countless times in striking editions, with just as striking jackets. For me, though, the first Random House book, published in 1952, stands head and shoulders above the rest – and that’s because of the arresting cover by master of Poster Art and graphic design, E. McKnight Kauffer.

A lovingly framed version of it hangs on the wall opposite me, as I type.

E. McKnight Kauffer – Poster Art boy

Although Edward (‘Ted’) McKnight Kauffer originally studied painting, first in his native America and later in Paris under the sponsorship of Professor Joseph McNight, whose surname he later adopted, he was to become best known as a celebrated and influential poster artist, particularly in the 1920s and 30s. Anthony Blunt called him the ‘Picasso of advertising design’.

Forced to break his studies by the outbreak of World War I, in 1914, McNight Kauffer moved to Britain rather than return to America. There, he was introduced by poster artist John Hassall to Frank Pick, Publicity Manager for London Underground Electric Railways. Pick was an advocate of progressive design: he commissioned Edward Johnston to design a special sans serif font and logo for London Underground (both of which are still in use) and, under his aegis, a stream of talented artists and graphic designers created beautiful artwork, promoting transport in London.

In 1915, Pick commissioned McNight Kauffer to create four posters – ‘Oxhey Woods’, ‘In Watford’, ‘Reigate; Route 60’ and ‘North Downs. For the next 25 years, McNight Kauffer worked for London Transport, during which time he produced 140 arresting posters for it, in addition to the various artworks created for other organisations. The latter included ‘Flight’ (1919), arguably one of the artist’s most recognised works and today iconic in modern graphic design. Publisher Francis Meynall used it on a poster campaign for the Labour Party’s The Daily Herald to promote hope in postwar Britain. It was subtitled ‘Soaring to Success – The Early Bird’.

As McNight Kauffer’s style evolved, it showed evidence of his various interests and influences, drawing on techniques found not just in traditional Poster Art, but in Cubism, post-expressionist, Vorticism and even Japanese woodcuts. He also began to incorporate typography into his work. He soon became known as much for innovative graphic design, as for Poster Art and his work was prominent in the advertising and promotion of important companies like Shell and BP, to name but a few.

Following the outbreak of World War II, in 1939, McNight Kauffer returned to the States, where he initially floundered. The American design industry was significantly more conservative than in Europe and he struggled to find anyone who understood his innovative work. Thankfully, his experiences changed in the early 1950s, when he was commissioned to produced posters for American Airlines, which remained his major client until his death in 1954, and for which he produced the gorgeous, striking posters that were to establish his reputation in the States as an influential graphic designer and commercial artist.

The book jacket – or ‘mini poster’

From the 1920s, McNight Kauffer’s work also began to appear on and in books. He illustrated several of his great friend TS Eliot’s Ariel poems (1927–31), published as a series of pamphlets. He considered the book jacket a ‘mini poster’, which is probably why covers such as Ellison’s Invisible Man translate so effortlessly to wall art.

From 1928 through to the early 1950s, McNight Kauffer designed more than 30 dust jackets for the Modern Library, including: Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca; Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon; Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and Richard Wright’s Native Son.

In 1952, McNight Kauffer illustrated Ralph Ellison’s seminal work Invisible Man for Random House. The deceptively simple cover is arresting (like the book’s contents), the use of colour restrained, yet cleverly designed to catch and hold the eye. The deconstructed face shows obvious Cubist and post-expressionist influences and evokes Harlem and the Jazz Age.

It is a cover that stands the test of time. It’s certainly one of my favourites, as is the novel itself.

On that, here’s a reminder of how brilliant Ellison’s writing is:

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.”

It just doesn’t get better than that.

Book covers we love: ‘Georgette Heyer’s Frederica – Arthur Barbosa (1965)‘; Dorothy L. Sayers’ Busman’s Honeymoon by Romek Marber (1963).

See also: ‘Books that changed my life’ board, Pinterest; articles: ‘How Penguin learned to fly – Allen Lane and the Original Penguin 10‘; ‘Romek Marber’

Notice: Please note the images and quotations included in this article are for promotional purposes only and are intended as a homage to the designers, artists and writers cited. In no way, have we have intentionally breached anyone’s copyright.

This article is ©The Literary Shed, 2014. It can only be reproduced with our permission. Please contact us if you wish to do so. We must be fully credited.